Improving Videos: How Can I Improve Videos I've Already Made?

If you have existing multimedia course content that you want to reuse, here are recommendations for repurposing and improving them for future courses.

There are a variety of reasons you might want to revisit a video you've recorded previously. Maybe it serves as pertinent remedial material for one of your courses. Maybe you've been asked by your department chair to convert one of your in-person courses into an online course. Maybe you want to include it as supplemental material in a different course. Whatever the reason, there are some things you can do to improve the efficacy of your existing videos if you don't have the time to re-record them.

If you're familiar with the cognitive theory of multimedia learning, then you're aware that our system for processing multimedia messages is a dual channel, limited capacity, active processing system. To effectively leverage this system, instructional multimedia messages need to be crafted to split cognitive load effectively between pictures and spoken words and carefully manage the speed and quantity of information being presented at any given moment. This theoretical framework provides the foundation for our recommendations on how you can improve your existing videos.

The Short Version

Assuming you're not able to re-shoot your videos (and that you're not working with a professional editor), here are some ideas to quickly improve their efficacy:

- Split up longer videos. Make sure nothing is longer than 20 minutes.

- Add chapters. They can help students organize the information.

- Add quiz questions. They promote engagement.

- Eliminate extraneous or unassessed content. Encourage students to dive deeper into what's important.

- Correct the transcript. It's good for the students and useful to you.

- Create generative activities to pair with videos. If in-video quiz questions aren't your thing, there are other options.

- Leverage - but don't reuse - lecture capture videos. Try to only use videos that are designed for the online modality.

Split Up Longer Videos

Most instructors are familiar with the best practice of "chunking." In multimedia research literature, this is more formally referred to as segmenting: breaking up your material into smaller pieces to aid learning. This is a best practice in part because our limited cognitive capacity can only allow us to deal with so much information at one time. The more we break it up, the easier it is to learn.

Segmentation is one of the strategies that arises out of cognitive load theory, specifically as a strategy to manage intrinsic load, or the cognitive effort that it takes to hold the entirety of the concept that the learner is encountering in working memory. So the more complex something is, the more cognitive effort must be devoted to just "carving out the mental space" to try and learn it. So the way you can improve learning is to break down your material into more "bite-size" chunks.

During course design, segmenting should be applied on multiple levels to multimedia materials (indeed, to all instructional materials), from the visual aids you use to the length of your video. So among other things, during this "pre-production" phase you'd presumably ensure that the focus of each video was narrow (to ensure it's short) and that your visuals minimize the amount of information on each slide.

In a pinch, though, you can accomplish some segmenting by turning some of your longer videos into multiple, smaller videos. As we said in our article on video length, educational videos should be no longer than 20 minutes, and ideally less than 12. So if you've got any videos over 20 minutes long, consider splitting them up into multiple clips. UCSD instructors can use Kaltura's video editor to split videos into multiple clips and then create playlists of their Kaltura media within a course's Media Gallery to group them together (which helps highlight their conceptual connection to one another).

Do be aware of a tip we discuss later, though, about not re-using lecture capture videos!

Add Chapters

Based on a large series of experiments and research, prominent multimedia learning researcher Richard Mayer identifies 12 principles of multimedia learning. One is called the signaling principle, which states that "people learn better when cues that highlight the organization of the essential material are added" (Mayer, 2009). Signaling can optimize students' generative load - the cognitive effort they spend to select, organize, and integrate words and pictures - by helping them understand what they should pay attention to and connect what you're saying with what they're looking at.

There are a variety of course design takeaways based on the signaling principle. Most have to do with making sure that your visual aids draw your students' attention to relevant information, such as with circles, arrows, highlights, text animations, or even verbal cues. When it comes to existing videos, though, one quick addition that can optimize your students' generative load is to add chapters.

Chapters reveal the organization of your content and serve as an advance organizer, which can guide the intake of information. As Ambrose et al note in their book How Learning Works, "when students are provided with an organizational structure in which to fit new knowledge, they learn more effectively and efficiently then when they are left to deduce this conceptual structure for themselves" (2010). Think of chapters as basically creating "slots" for the knowledge and skills you intend to teach them in the video.

Luckily, if you're a UCSD community member, Kaltura allows you to add chapters pretty easily to your media. Check out our knowledge base article on adding chapters if you want to learn how.

Add Quiz Questions

Something else you can do to improve your existing videos is to add quiz questions to them. While this is somewhat technology-dependent, UCSD users are able to create video quizzes by leveraging Kaltura. (Check out our KBA on how to create an in-video quiz if you're interested.)

Adding questions to your videos can serve a variety of purposes. The first (and perhaps most obvious) benefit is that it prepares students for your larger summative assessments. While they can certainly reduce their anxiety about the assessments, they may also see improved performance thanks to the testing effect: the idea that answering practice questions can "strengthen connections among the elements of to-be-learned information and one's existing knowledge, resulting in better long-term learning" (Fiorella, 2022).

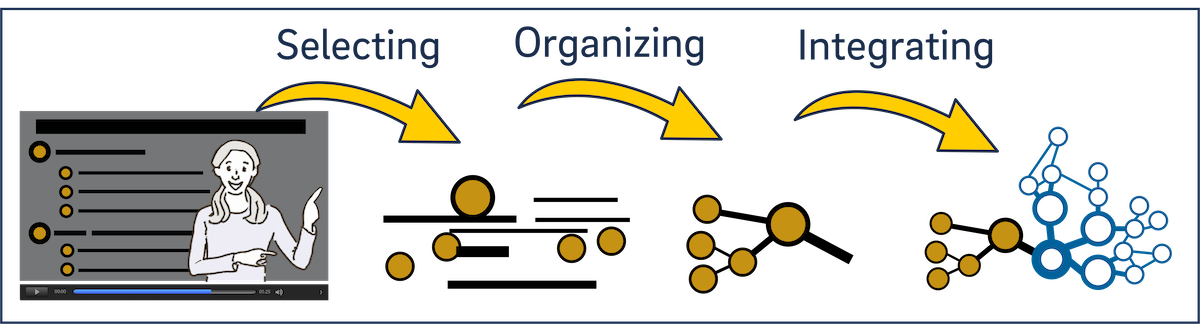

Inserting quiz questions into videos also help to encourage students to engage in active processing while watching videos. If you recall from our article on multimedia learning principles, "active processing" is the cognitive effort involved with selecting relevant information from a multimedia message, organizing it into a coherent schema, and integrating that schema with schemata in long-term memory. It forces students to begin applying what they're learning, "explicitly converting video watching from a passive to an active-learning event" (Brame, 2016).

In-video quiz questions can also be valuable because in addition to promoting active processing, they also implicitly encourage students to be active learners. That is, they may be more likely to engage in behaviors to foster active learning, such as listening more attentively and taking notes. Many students have the misconception that they're able to learn better through video and subsequently experience a sense of overconfidence in their learning. With this in mind (whether or not you include quiz questions), it's definitely worth reminding students that the videos in the course are a core "text" for the course and that they should pay attention closely and take notes just as most of them would at a live lecture.

Eliminate Extraneous or Unassessed Content

One of the tenets of cognitive load theory (as it pertains to designing educational materials) is that instructors should eliminate material that doesn't support learning goals. This can be done in a variety of ways, from removing background music to eliminating entire reading assignments. When it comes to your existing videos, though, consider removing any content that's not directly tied to your learning objectives.

Even a humorous anecdote may be worth putting on the chopping block. Multimedia researchers use the notable term seductive details to refer to "interesting but irrelevant material that is added to a passage in order to spice it up" (Mayer, 2009). Intuition suggests that enhancing learners' attention or arousal with entertainment will improve learning, but the opposite is often true.

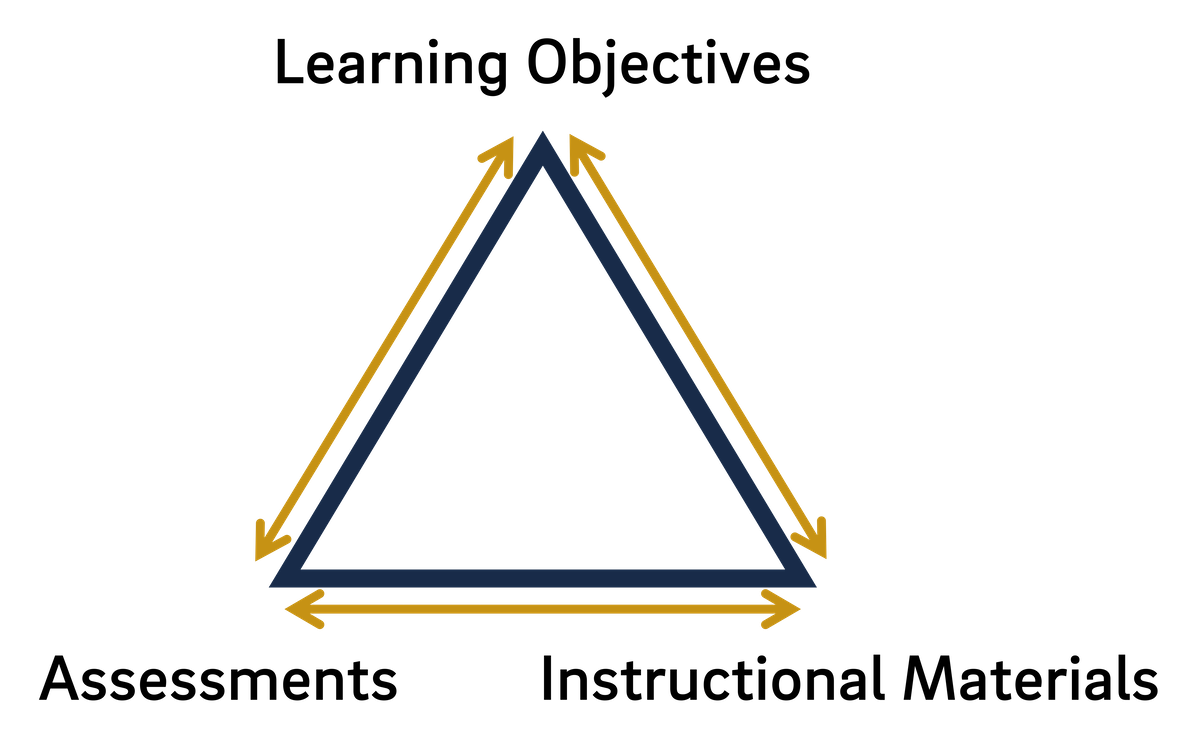

A good question to ask when considering what material to remove is whether students are tested on it. While most instructors are familiar with the notion of backwards design - beginning course design with where you want the students to end up - the principle that underpins this method is that of alignment between the three main components of course design: your instructional materials should prepare students for your assessments, which in turn should demonstrate their progress toward your learning objectives. So if there's any content in your course that is unassessed, it likely doesn't align with your learning objectives and can be eliminated.

As has been stated frequently in this article and elsewhere, we have a limited cognitive capacity for learning, and that capacity is even lower for novice learners. Accordingly, less is more. Providing students with less material will allow you - and them - to dive deeper into the content that remains.

As in our suggestion to split up longer videos, UCSD community members can use Kaltura's video editor to remove parts of existing videos.

Correct the Transcript

If you're a UCSD community member using Kaltura, any video you upload to your media repository will automatically receive "machine captions" - captions generated by software and not reviewed by a human. The accuracy can vary considerably depending on a variety of factors, such as your speaker's accent, the complexity of the subject matter, your speaking speed, and many others, but the average accuracy is generally said to be between 70 and 80%.

With this in mind, when revisiting old videos, it's worth updating the transcript. Doing so can provide two key benefits: you make your video fully accessible, and you can provide a text-based equivalent alternative to your students.

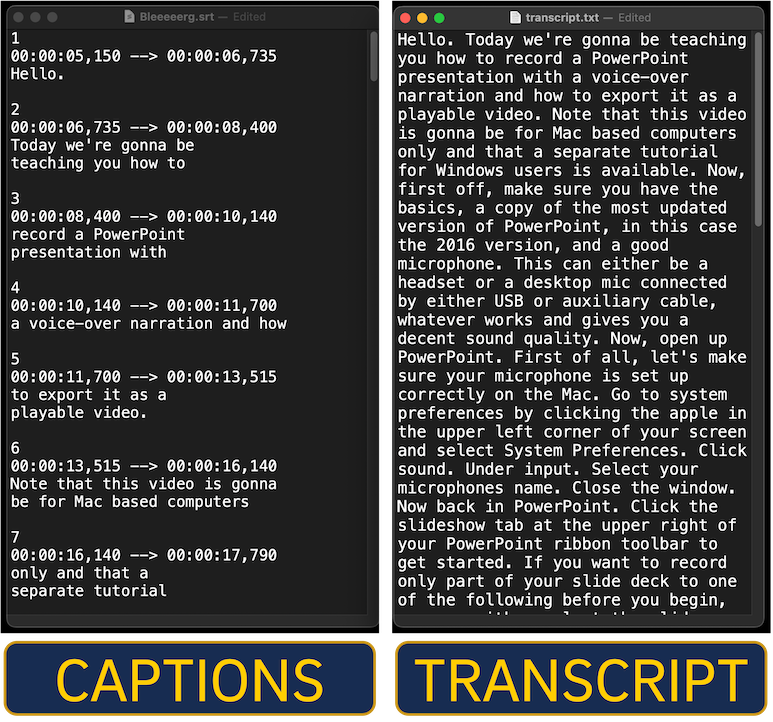

Now, we've already used two different terms to refer to the words that represent what's been said during a video: captions and transcripts. We'll explain why we recommend you edit the transcript rather than the captions in a moment, but it's important to draw a distinction between the two terms, particularly since they're often mistakenly used interchangeably.

While both refer to a textual representation of words spoken during a video, here's where they diverge:

- Caption files contain timecodes that indicate the start and endpoints of when a piece of text should be on the screen while the video is playing. They can have a variety of file extensions, such as .srt or .vtt.

- Transcript files contain no timecodes at all, and usually have a .txt file extension. They often contain just a big block of text without any paragraph breaks.

Kaltura generates a transcript for an entry based on the captions. So if you edit the captions, the changes will be reflected in the transcript. One nice feature, however, is that you're able to upload pure text to a Kaltura entry and ask the system to generate the timings. In other words, you can upload a transcript and have Kaltura generate the caption file.

It's particularly nice because it's easier to edit a transcript than a caption file. When you're editing captions, you're obviously listening to your video and making changes, but there's a lot of scrolling and you have to navigate your way around the time codes (which you generally don't want to change). When you're editing a transcript, though, you're just editing the text.

But beyond simply correcting the words and grammar, you can also add paragraph breaks. When you're done, then, you have a document that you could present to the students as an equivalent alternative to watching the video. You may have seen a discussion of equivalent alternatives in our article on effective types of educational videos, but in short, a course design principle that emerges from the instructional design framework of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is that it's helpful for the variety of students in your courses to have choices in how they consume your materials. Offering a text version in addition to a video version can address more learning styles and can be particularly helpful for more challenging material.

It's essential, though, that the text version of your video be equivalent. That is, the educational content between the two has to be the same. It can't be better or worse to, say, watch the video instead of reading the text. So consider dropping images into the text as needed (in which case you'll want to copy and paste the text from that .txt file into a Word document.)

In addition, as AI technology continues to grow, text-based versions of your materials might be quite advantageous for developing quiz questions, study guides, or summaries, to name just a few. That said, the benefits of correcting the text version of what was said in your video can provide a variety of advantages for both you and your students.

Create Generative Activities to Pair with Videos

We already discussed inserting quiz questions directly into a video. This suggestion obviously depends on what kind of technology to which you have access, and the reliability of that technology. Adding these questions, though, falls under a larger umbrella of ensuring that your videos have an accompanying "generative activity."

You may recall from our discussion of cognitive load theory that there are three types of "load" that impinge on our limited capacity to process pictures and words:

- Intrinsic load: the amount of cognitive effort required to hold the overarching concept in working memory

- Generative load: the effort required to select, organize, and integrate information with prior knowledge

- Extraneous load: cognitive effort wasted on things that don't support the learning goals

Generative load, then, largely refers to the conscious effort involved in trying to learn new information. The hope is that your material - be it a video, a live lecture, or a reading - inspires your students to engage in this active learning process. But this doesn't always occur, or students' unfamiliarity with the material may impede their ability to do so. With this in mind, it's important to consider creating "generative activities" that explicitly encourage students to engage in this process.

This recommendation is grounded in generative learning theory, which posits that learning is an "active process of inference generation," during which students connect the pieces of what they're learning with each other and also build connections between that new material and their prior knowledge (Mayer & Fiorella, 2022). Subsequently, the generative activity principle that emerges from this theoretical framework posits that "multimedia lessons will be most effective when they provide students explicit opportunities to engage in appropriate generative activities during learning" (Mayer & Fiorella, 2022). So it's not enough to assume students will engage in cognitive activity that allows them to make sense of what you're teaching.

There are a variety of generative activities you can offer, such as self-testing, self-explaining, using spatial note-taking strategies, responding to specific practice questions before, during, or after a video lesson, and creating a verbal explanation or visual representation (Fiorella, 2022). If you want to think more broadly about this, consider activities that fit within these three high-level categories (Mayer & Fiorella, 2022):

- Verbalizing: using spoken words to summarize, self-explain, or teach

- Visualizing: generating drawings, maps, or mental models (by imagining)

- Enacting: gesturing or manipulating body movements or physical objects

From a technical perspective, you can add these activities in a variety of ways. You can leverage Kaltura's features to create in-video quizzes. (Remember that you have the option of adding so-called "reflective" questions, which don't require any submission on the part of the viewer.) You can break up your video into pieces and add a Canvas quiz in between them within the module. You could embed the video at the TOP of a Canvas quiz. You could ask students to record a video (or audio recording) of themselves completing an activity.

The generative activity principle argues, at its core, that even the most well-designed video may not be sufficient to prompt students to engage in generative processing, and that paired activities may benefit - or even be necessary for - learners trying to make sense of new or complex material. As Mayer and Fiorella argue, "prompting students to generate task-relevant words, visuals, and/or movements during learning encourages students to relate the material to their existing knowledge, resulting in deeper learning than passive environments that do not incorporate generative activities" (2022).

Leverage - But Don't Reuse - Lecture Capture Videos

It's generally inadvisable to re-use lecture capture videos for subsequent classes. In a way, there's a "suspension of disbelief" for effective course videos that the instructor is speaking to the student directly, creating a sense of partnership and a motivation to engage with the material. While this social agency is accomplished in a variety of ways - largely through cues like a casual tone and eye contact with the camera - it can be undermined by using a lecture that was clearly performed for others. Such a video "may feel less engaging than a video that is created with an online environment as the initial target" (Guo et al, 2014).

The bottom line is that if you're including videos in your online, remote, or hybrid course, they should ideally have been designed with the online environment in mind. "Instructors can also promote student engagement with educational videos by creating or packaging them in a way that conveys that the material is for these students in this class" (Brame, 2016). Lecturing to a classroom of people has a different feel than a video that's supposedly meant to be watched by one student at a time. If you have a choice, try to avoid re-using lecture capture videos.

That doesn't mean that they're not useful. You can download the transcript for the video and review it to develop more segmented videos in the future. Or you could turn part of that transcript into a document for students to read, instead of watching a video. (Remember, lecture in and of itself isn't a great use of the video medium.) You may also find that some student questions that occurred during the class are valuable to address in a separate video - if you've read our article on effective course videos you'll know that addressing misconceptions is an excellent use of video.

Since the pandemic, many instructors are now far more familiar with the practice of making videos for their courses. It's likely, then, that you, as an instructor, have a large collection of videos, perhaps at varying levels of sophistication. While the ideal situation for any online, remote, or hybrid course is to create videos specifically for that course, the most precious commodity for instructors is time. If you're short on it, consider the suggestions above for ways to improve your videos and enhance your students' learning.

References

Ambrose, Susan A., Bridges, Michael W., DiPietro, Michele, Lovett, Marsha C., & Norman, Marie K. (2010). How learning works: 7 research-based principles for smart teaching. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Brame, C. J. (2016). Effective educational videos: Principles and guidelines for maximizing student learning from video content. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 15(4). https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.16-03-0125

Fiorella, L. (2022). Multimedia Learning with Instructional Video. In R. E. Mayer & L. Fiorella (Eds.), The Cambridge Handbook of Multimedia Learning (pp. 487–497). Essay, Cambridge University Press.

Guo, P. J., Kim, J., & Rubin, R. (2014). How video production affects student engagement. Proceedings of the First ACM Conference on Learning @ Scale Conference, 41–50. https://doi.org/10.1145/2556325.2566239

Mayer, R. E. (2009). Multimedia learning (2nd ed.). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Mayer, R. E. and Fiorella, L. (2022). The Generative Activity Principle in Multimedia Learning. In The Cambridge Handbook of Multimedia Learning (pp. 339–350). Essay, Cambridge University Press.

Have additional questions about video? Contact Multimedia Services at multimedia@ucsd.edu.